Brushstrokes of violence: Artists’ Portrayals of War

Before photography became widespread and could capture events for a broad audience, the responsibility of illustrating significant moments fell to artists - painters and sculptors. Today, numerous works by these artists reflect their responses to military violence, conveying the sentiments of their era. Let’s explore three of the most renowned examples in European art that depict violence and war.

“The Third of May 1808”

El Tres de Mayo, by Francisco de Goya

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18777858

In 1808, the reign of Charles IV was compromised, most notably by the reputation of his prime minister, Manuel de Godoy. Godoy was unpopular both among Spain’s aristocratic circles and the Spanish people for numerous reasons. The aristocracy resented him for obtaining power despite being born in poverty, while the general populace resented his ambitious and opportunistic nature and his desire to ally with revolutionary and atheistic France against Christian Great Britain.

Coupled with an economic crisis that led to decreased industrial production and food shortages, these factors culminated in the uprising of Aranjuez. In March 1808, Spain saw the fall of King Charles and his wife Maria, and the throne was taken by their son, Ferdinand VII, a participant in the tumult. The internal struggles of the royal family created a perfect opportunity for Napoleon I, leading to the occupation of Spain and the appointment of Napoleon’s brother as King of Spain.

“The Third of May 1808” was the response of the famous painter Francisco Goya to the events that took place near Principe Pio Hill in Madrid—the execution of Spanish insurgents by French occupying forces. Goya spent a lot of time recording the atrocities during the French occupation and his series, “The Disasters of War”, is an unadulterated illustration of the horrors of war, perhaps the most honest work Europe had seen at the time.

The Second of May 1808 was completed in 1814 and depicts the uprising that precipitated the executions of the third of May.

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6342190

“The Third of May 1808” is his most notorious piece of propaganda—it champions the battle of the Spaniards for freedom and shows the ugly face of military violence. The focal point of the painting is the martyr with stigmata on his palms, assuming a Christ-like pose. The French are depicted as faceless, almost inhuman creatures in uniform, while the Spaniards are depicted vibrantly and humanely.

Even though Goya was previously sympathetic to the French, the events of 1808, and the blood that flowed through the streets of Madrid after the massacre, left a profound impression on him and his art. His painting is now one of the most famous depictions of real events in European art history.

“Guernica”

On April 26, 1937, the town of Guernica was heavily bombarded by Francisco Franco’s Nationalist faction allies—the Nazi German Luftwaffe's Condor Legion and the Fascist Italian Aviazione Legionaria. The bombing targeted the civilian population, as well as military targets, in a nearly three-hour-long blitzkrieg. During that period, Spain was in the middle of a brutal civil war, and this event helped Franco’s rebels capture northern Spain.

Guernica in ruins, 1937

By Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H25224 / Unknown author / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5434009

The bombing became widely known internationally not only due to its nature but in part thanks to its depiction by Pablo Picasso in his famous work “Guernica”. Picasso was living in Paris during these tumultuous times for Spain and was approached by the Spanish republican government with a commission to produce a mural for Spain’s pavilion at the World Fair in Paris in 1937. Their goal was to affirm their legitimacy in international eyes and to condemn the brutal warfare led by Franco and his rebels.

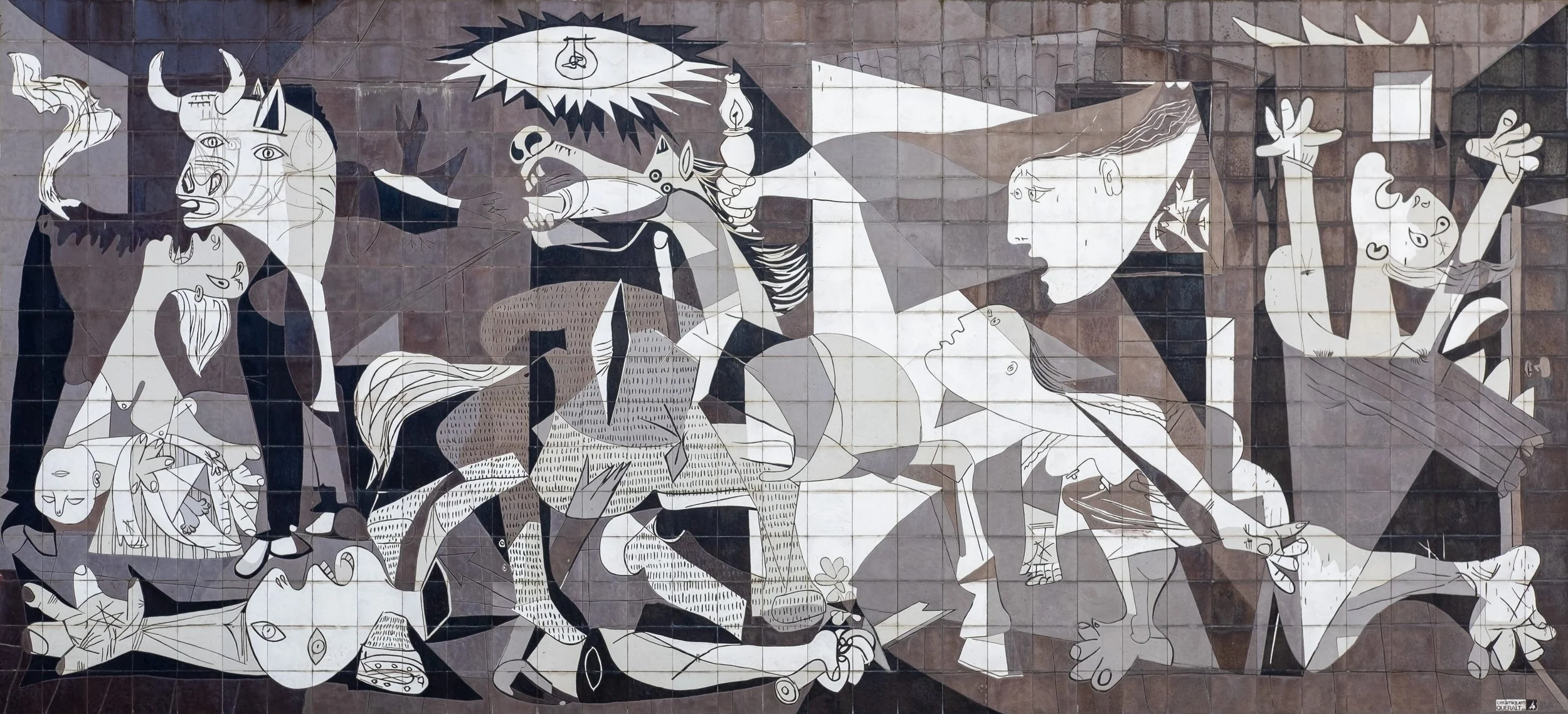

Picasso, even though being known as an artist who wasn’t keen on mixing politics with his art, accepted. Several months later, the gruesome bombing of Guernica was carried out, and it became the theme of Picasso’s depiction of the events in Spain. True to his style, Picasso created an abstract painting with cubist figures and an unusual representation of space, in a neutral monochrome palette. The center of the painting is focused on a horse stumbling over a fallen soldier, illuminated by the rays of a light bulb. We can also see a bull encompassing a wailing mother carrying a slack child in her arms. Another part of the painting features a ghostly figure carrying a gaslight next to a woman who hangs her arms in despair. Behind them, a howling figure is consumed by fire and ruins.

A mural of Picasso’s “Guernica”

By Jules Verne Times Two / www.julesvernex2.com, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=149356484

This painting creates the feeling that it is an emotional response to war and violence, even if it’s created in Picasso’s abstract style. At the Paris fair, it was received with mixed sentiments. After the fair ended and before the Spanish republican government conceded to Franco’s nationalists, they toured it around Europe to create awareness of the political events in Spain and to raise support for their cause.

Picasso himself was worried about the fate of the painting. He refused to allow it to be presented in Spain while Franco was in power and vowed to return it once the republic was restored. Following the Nazi occupation of France, he loaned the painting to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, which spent the next 20 years touring it around the USA and internationally. During that period, “Guernica” gained notoriety and sparked massive interest in Picasso’s technique and the symbols he used to depict the gruesome event.

Unfortunately, Picasso died two years before the fall of Franco, and he never got to witness the restoration of Spain.

After years of negotiations, the painting was returned to Spain and is now part of the collection of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.

“The Execution of Emperor Maximilian”

The mid-19th century was an interesting period in Mexico’s history. Following the three-year-long civil war (1858-1861), the conservatives lost on the battlefield and sought allies outside of Mexico in a bid to oust the liberal government. This was an opportunity for Napoleon III, who sought to intervene in Mexico and set up a French puppet regime with conservative support.

In their search for a European head of state, the Mexican monarchists met with Napoleon III and Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph of Austria—an Austrian archduke and member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine. Ferdinand Maximilian was the younger brother of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria but was removed from his duties as commander of the Imperial Austrian navy and viceroy of Lombardy-Venetia by the former.

Maximilian’s heritage made him a prime candidate for the plan of the Mexican monarchists. He was a descendant of Charles V - the Emperor who conquered the Aztecs and brought Mexico under Spanish rule. In 1863, he sailed to Mexico with the backing of the French military of Napoleon III, which sought to collect debts from the Mexican Government, and subsequently was installed as the Emperor of Mexico under the name Maximilian I.

Even though he had the backing of Napoleon and the Mexican conservatives, Maximilian showed naivety and no knowledge of the complex political struggles of Mexico. Believing that he would be widely accepted by the Mexican people, he sailed to his death, which occurred in the third year of his rule.

On the other hand, the Mexican resistance, which had installed Maximilian to power, failed to notice his liberal inclinations. He installed a liberal government and introduced a political program similar to that of his predecessor Benito Juarez.

In 1865, Juarez was driven far north into Texas by the French army, but this period marked the end of the American Civil War. The US government demanded the withdrawal of the French army on the grounds of violation of the Monroe Doctrine. The emperor failed to secure the backing of his brother and the Pope, and the French army eventually withdrew, leading to the return of Juarez and his army in Mexico City.

Maximilian refused to abdicate, was later captured with his entourage, and executed near Queretaro on June 19, 1867. It seems that Maximilian really believed he could be a good, just, and loyal ruler of the people of Mexico. Famously, his last words were, "I pray that my blood, which is about to be shed, will be shed for the good of this country. Long live Mexico! Long live independence!"

The story of Mexico’s Austrian Emperor inspired a series of paintings entitled “The Execution of Emperor Maximilian” by Édouard Manet. Manet started working on the paintings inspired by Goya’s “The Third of May 1808”. He was averse to Napoleon III’s imperial interventions, and it is noticeable that in one of the paintings, the person preparing for the final shot has a striking similarity to the French Emperor.

“The Execution of Emperor Maximilian” (1868–69), oil on canvas, 252 × 305 cm. Kunsthalle Mannheim

By Édouard Manet - The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=154405

Manet depicted the execution in a very interesting manner. The paintings illustrate the event in an ambiguous way - while the execution was a gruesome scene and an act of notable political importance, it exudes an almost nonchalant sentiment, judging by the pose of an officer in one of the paintings and the apathetic appearance of the spectators.

The series consists of three large oil paintings, but Manet also produced a small oil sketch and a lithograph. Today, each painting is part of the collection of a different gallery—the Kunsthalle in Mannheim, the National Gallery in London, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.